It has often been said of technology standards that the good thing is that there are just so many to pick from! The same is true, to perhaps a more limited extent, in the world of cryptography. The choices may not be quite so diverse, but there are still many crypto algorithms to choose from.

There are several reasons for this variation. One justification for this variation is that knowledge of the weakness in a cryptographic algorithm is very often a closely guarded secret itself, in an effort to encourage others to unwittingly use an algorithm where the ciphertext can be deciphered. There are crypto algorithms promoted by national communities in the view that use of a “home grown” algorithm is better in some sense (such as GOST, developed in the 1970’s in the USSR as a Soviet alternative to the US-developed DES). Some algorithms are seen as being harder to decrypt than others. Some are seen as being more resistant to decryption using quantum-computing techniques. Some impose more work on the encryptor to generate the cyphertext.

Standards bodies have responded to this situation by avoiding, where possible, specifying any single crypto algorithm in their specifications, making the choice of algorithm a decision made by the entity performing the encryption, or more often the result of a decision made by a software developer.

The implication of this choice of crypto algorithms is that the parties performing decryption need to perform a dialogue with the encryptor to agree to use an algorithm that both entities support and is acceptable to both. This real-time dialogue between the communicating parties is not always an option, and the RPKI (Resource Public Key Infrastructure) is a good case in point. In the RPKI a user of the system needs to support all crypto algorithms that could be used by the various parties that are signing data. A similar constraint applies in DNSSEC, where the validating resolver must support all crypto algorithms used by signers.

This poses some logistical challenges when attempting to introduce a new crypto algorithm into these common spaces, such as DNSSEC. There is little benefit in using an algorithm to generate a digital signature if no one can validate it, and equally there is little point in adding support for an algorithm into a validator if no one is using it to sign anything. Neither signers nor clients are motivated to move first. The result is that without a specific prompt, such as knowledge of some form of algorithm weakness, the process of adoption tends to be a protracted one.

This appears to be the case with the introduction of Elliptical Curve crypto algorithms in DNSSEC. When we first looked at this topic with a measurement study of the level of support for the elliptical curve algorithm ECDSA P-256 in 2014, the study concluded that ECDSA was not a viable crypto algorithm for use in DNSSEC at that time. There were too few DNSSEC validators who could validate data signed with this algorithm, as the user-based measurement indicated that some 25% of users who validated with RSA were not validating with ECDSA. Some four years later, in 2018, we returned to this measurement, and this time the gap between support of RSA and ECDSA had narrowed to some 3% of the user base. The conclusion at that time was that ECDSA P-256 was indeed ready for use.

Has this picture changed in the three years since that study?

ECDSA Cryptography

ECDSA is a digital signature algorithm that is based on Elliptical Curve Cryptography (ECC). This form of cryptography is based on the algebraic structure of elliptic curves over finite fields.

The security of ECC depends on the ability to compute an elliptic curve point multiplication and the inability to compute the multiplicand given the original and product points. This is phrased as a discrete logarithm problem, solving the equation bk = g for an integer k when b and g are members of a finite group. Computing a solution for certain discrete logarithm problems is believed to be difficult, to the extent that no efficient general method for computing discrete logarithms on conventional computers is known (outside of potential approaches using quantum computing of course). The size of the elliptic curve determines the difficulty of the problem.

The major attraction of ECDSA is not necessarily in terms of any claims of superior robustness of the algorithm as compared to RSA, but in the observation that Elliptic Curve Cryptography allows for comparably difficult problems to be represented by considerably shorter key lengths. If the length of the keys being used is a problem, then maybe ECC is a possible solution.

“Current estimates are that ECDSA with curve P-256 has an approximate equivalent strength to RSA with 3072-bit keys. Using ECDSA with curve P-256 in DNSSEC has some advantages and disadvantages relative to using RSA with SHA-256 and with 3072-bit keys. ECDSA keys are much shorter than RSA keys; at this size, the difference is 256 versus 3072 bits. Similarly, ECDSA signatures are much shorter than RSA signatures. This is relevant because DNSSEC stores and transmits both keys and signatures.”

RFC 6605, “Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) for DNSSEC”, P. Hoffman, W.C.A. Wijngaards, April 2012

We are probably justified in being concerned over ever-expanding key sizes in RSA, and the associated implications of the consequent forced use of UDP fragments for the DNS when packing those longer key values into DNSSEC-signed responses. If UDP fragmentation in the DNS is unpalatable, then TCP for the DNS may not be much better, given that we have no clear idea of the scalability issues in replacing the stateless datagram transaction model of the DNS with that of a session state associated with each and every DNS query. The combination of these factors makes the shorter key sizes in ECDSA an attractive cryptographic algorithm for use in DNSSEC.

Crypto Algorithms and DNSSEC

To help understand the relative strength of cryptographic algorithms and keys there is the concept of a security level which is the log base 2 of the number of operations to solve a cryptographic challenge. In other words, a security level of n implies that it will take 2n operations to solve the cryptographic challenge

Using larger keys in crypto has several implications when we are talking about the DNS. Larger keys mean larger DNS signatures and larger payloads, particularly for the DNSKEY records. A comparison of DNSSEC signature record sizes for RSA with a number of different key sizes and both Elliptical and Edwards curve algorithms is shown in Table 1.

| Algorithm | Private Key | Public Key | Signature | Security Level (bits) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSA-1024 | 1,102 | 438 | 259 | 80 |

| RSA-2048 | 1,776 | 620 | 403 | 112 |

| RSA-4096 | 3,312 | 967 | 744 | 140 |

| ECDSA P-256 | 187 | 353 | 146 | 128 |

| Ed25519 | 179 | 300 | 146 | 128 |

Table 1 – Crypto Sizes (Bytes)

ECDSA permits all of the DNSSEC resource records, namely RRSIG, NSEC(3), DNSKEY and DS records to all be under 512 bytes in length in most circumstances (the DNSKEY record during a keyroll is the exceptional case here).

Larger keys are not only a problem in the DNS transport area, but these larger keys also imply that it takes more time to both sign and validate signatures (see a recent report on this topic).

However, it should be noted that the security level given in Table 1 relates to conventional non-quantum computers and algorithms. Our current thinking about quantum computing capabilities is that some algorithms appear to be more resilient than others to quantum-based decryption efforts, and specifically RSA with larger keys may be more resilient than an equivalent strength ECDSA profile in this anticipated quantum computing environment.

While we are listing caveats to the interpretations of the data in Table 1, it is also useful to bear in mind the issue of security lifetime. When a piece of information is encrypted, it is vulnerable to attack over the period when the information remains valid. DNSSEC is not used to encrypt DNS data. From the perspective of DNSSEC, DNS data is public data and DNSSEC does not help at all to protect its secrecy. There are other mechanisms to provide channel security for DNS queries and responses (DNS over TLS, DNS over QUIC, and DNS over HTTPS) and other mechanisms to pull apart the association of who is making what DNS query (oblivious DNS). DNSSEC is specifically limited to protecting the data against tampering and a more limited protection against replay of stale DNS data.

This consideration implies that secure lifetime of a data item secured by a DNSSEC signature is based on the lifetime of the key that signs the data. The more frequently a zone admin rolls the keys, and the shorter the signature validity periods, then the shorter the time window available for an attacker to crack the algorithm and manufacture bogus DNS records that appear to be validly signed.

This then gives zone administrators a trade-off in terms of anticipated secure lifetimes for their choice of crypto algorithm profiles. More secure keys have a longer anticipated secure lifetime, but the larger DNS records may cause DNS failures within the transport issues in handling large DNS payloads. If the keys are rolled regularly, then the window of opportunity for attack is shortened, and the secure lifetime need only be of the same order of length as key lifetimes specified in the zone. This would allow the continued use of key profiles that have a secure lifetime much shorter than 10 years. In this latter scenario the choice of a shorter key also places an obligation on the zone administrator to perform regular keyrolls within the selected design parameters, ensuring that an attacker does not have sufficient time to break the encryption profile for each iteration of the key value.

Every DNSSEC Validator Supports RSA

While it is up to the DNSSEC validator to determine what crypto algorithms it supports, there is one aspect of DNSSEC where there is no real choice, and that is the algorithm used to sign the root zone. If the validator does not support RSA, then it cannot complete the construction of the interlocking signatures that connect the trust anchor, namely the root zone’s Key-Signing Key, to the DNSSEC signature being validated.

The implication from this observation is simple: Every DNSSEC validator must support the RSA algorithm.

So, when we look at a comparison between validation support for RSA and ECDSA in the DNS then the question is in fact a question about the level of support for ECDSA.

With that in mind let’s proceed.

The ECDSA Measurement

The question posed here is: what proportion of the Internet’s end users use security-aware DNS resolvers that are capable of handling objects signed using the ECDSA protocol, as compared to the level of support for the RSA protocol?

At APNIC Labs, we’ve been continuously measuring the extent of deployment of DNSSEC for a couple of years now. The measurement is undertaken using an online advertising network to pass the user’s browser a very small set of tasks to perform in the background that are phrased as the retrieval of simple URLs of invisible web “blots”. The DNS names loaded up in each ad impression are unique, so that DNS caches do not mask out client DNS requests from the authoritative name servers, and the subsequent URL fetch (assuming that the DNS name resolution was successful) is also a uniquely named URL so it will be served from the associated named web server and not from some intermediate web proxy.

Our DNSSEC test uses three URLs:

- a control URL using an unsigned DNS name,

- a positive URL, which uses a DNSSEC-signed DNS name, and

- a negative URL that uses a deliberately invalidly-signed DNS name.

A user who exclusively uses DNSSEC validating resolvers will fetch the first two URLs but not the third (as the DNS name for the third cannot be successfully resolved by DNSSEC-validating resolvers, due to its corrupted digital signature).

The negative test exposes an interesting side effect of DNS name resolution. There is no DNSSEC signature verification failure signal in the DNS, and the DNSSEC designers chose to adopt an existing error code to be backward compatible with existing DNS behaviors. The code chosen for DNSSEC validation failure is Response Code 2 (RCODE 2), otherwise known as SERVFAIL. In other DNS scenarios a SERVFAIL response means “the server you have selected is unable to answer you” which client resolvers interpret as a signal to resend the query to another server. Given that the validation failure will happen for all DNSSEC-enabled queries, the client stub resolver should iterate through all configured recursive resolvers while it attempts to resolve the name. If any of the resolvers is not performing DNSSEC validation the client will be able to resolve the name. So only users who exclusively use DNSSEC validating resolvers will fail to resolve this negative DNS name.

The authoritative name servers for these DNS names will see queries for the DNSSEC RRs (in particular, DNSKEY and DS) for the latter two URLs, assuming of course that the DNS name is unique and therefore is not held in any DNS resolver cache).

To test the extent to which ECDSA P-256 is supported we added two further tests to this set, so that we now have five tests:

- a control URL using an unsigned DNS name,

- a positive URL, which uses a DNSSEC-signed DNS name, signed with ECDSA P-256,

- a negative URL that uses a deliberately invalidly signed DNS name, signed with ECDSA P-256,

- a positive URL, which uses a DNSSEC-signed DNS name, signed with RSA-1024,

- a negative URL that uses a deliberately invalidly signed DNS, name signed with RSA-1024.

What do security-aware DNS resolvers do when they are confronted with a DNSSEC-signed zone whose signing algorithm is one they don’t recognize? RFC 4035 provides the answer this this question:

If the resolver does not support any of the algorithms listed in an authenticated DS RRset, then the resolver will not be able to verify the authentication path to the child zone. In this case, the resolver SHOULD treat the child zone as if it were unsigned.

RFC4035, “Protocol Modifications for the DNS Security Extensions”, R. Arends, et al, March 2005.

A DNSSEC-validating DNS resolver that does not recognize the ECDSA algorithm should function as if the name was unsigned and return the resolution response. We should expect to see a user who uses such DNS resolvers to fetch the web objects for both the positive and negative URLs.

Missing ECDSA Support by Economy

We conducted a measurement in the first 10 days of October, comparing the level of support for RSA-1024 (where we do not anticipate issues with UDP fragmentation or DNS truncation) with ECDSA P-256.

The overall measurement was conducted across 94 million endpoints. The sample data was weighted by estimated national user populations in an effort to mitigate sampling bias inherent in the sampling system that underlies this measurement system.

The results were similar to the picture we obtained in 2018. DNSSEC validation is supported by the resolvers used by 29.8% of users. These users appear not to be able to resolve a DNS name if it is invalidly signed and are seen to launch queries consistent with the DNSSEC validation function. This figure drops to 26.8% of users when ECDSA P-256 is used as the singing algorithm. This 3.0% variation in the user population is consistent with the 3% variation that was observed three years ago, so it appears that very little has changed in this respect over the last three years.

When viewed at a level of national communities there were 70 economies where the variance in ECDSA support by users within that economy was greater than 1% of the user population in that economy. This is perhaps too fine a filter level as the noise factors in this experiment given an uncertainty factor of a roughly estimated 5%. Using this 5% of users as a threshold filter, then the number drops to 38 such economies. Table 2 lists those 25 economies with the greatest level of variation of support between these two algorithms.

| CC | Difference | RSA-1024 | ECDSA | Raw Samples | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM | 34% | 37% | 3% | 6,974 | Oman |

| UZ | 31% | 51% | 20% | 5,095 | Uzbekistan |

| JO | 25% | 28% | 2% | 18,241 | Jordan |

| PT | 24% | 68% | 44% | 102,570 | Portugal |

| BT | 22% | 96% | 74% | 1,143 | Bhutan |

| ZA | 21% | 54% | 32% | 39,552 | South Africa |

| FJ | 20% | 90% | 70% | 1,960 | Fiji |

| SG | 19% | 71% | 52% | 12,897 | Singapore |

| IT | 18% | 33% | 14% | 72,002 | Italy |

| HK | 18% | 68% | 50% | 21,215 | Hong Kong |

| YE | 16% | 59% | 43% | 7,509 | Yemen |

| IQ | 15% | 74% | 58% | 158,902 | Iraq |

| QA | 15% | 20% | 4% | 7,434 | Qatar |

| BD | 15% | 57% | 42% | 344,653 | Bangladesh |

| NZ | 15% | 85% | 69% | 2,295 | New Zealand |

| MV | 13% | 47% | 34% | 2,794 | Maldives |

| KH | 13% | 47% | 34% | 20,409 | Cambodia |

| AZ | 12% | 51% | 38% | 31,634 | Azerbaijan |

| GE | 12% | 50% | 37% | 16,649 | Georgia |

| CL | 11% | 19% | 7% | 4,986 | Chile |

| CH | 11% | 74% | 62% | 7,657 | Switzerland |

| BH | 10% | 27% | 16% | 5,665 | Bahrain |

| PS | 10% | 40% | 30% | 15,837 | Palestine |

| SK | 10% | 25% | 15% | 31,003 | Slovakia |

Table 2 – Variation in support between RSA-1024 and ECDSA P-256 between economies

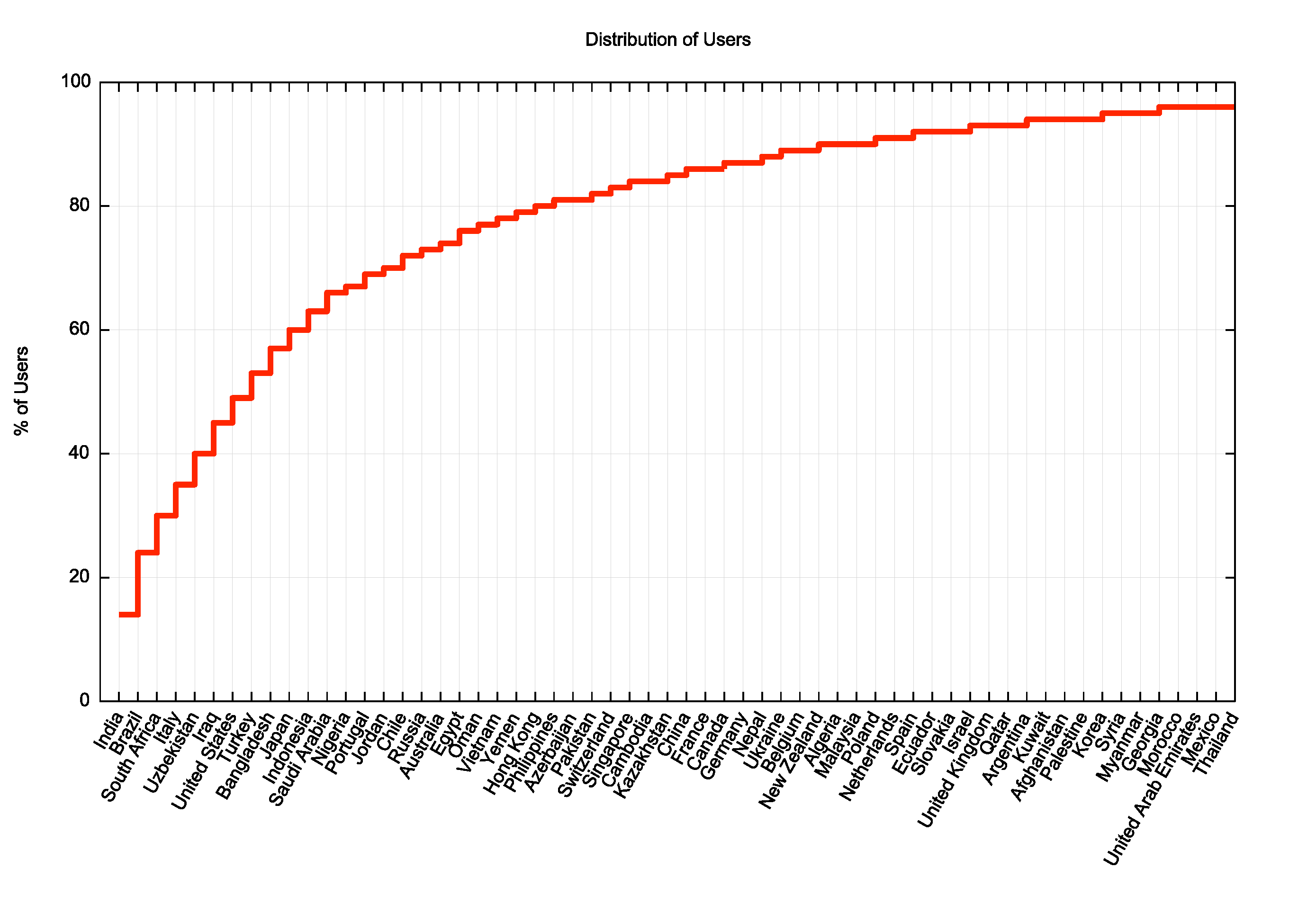

As well as looking at this table in a tabular form, we can weight these numbers by using the estimated national user population. This 3.0% of users corresponds to an estimated pool of 147M users. The cumulative distribution of where these users are located is shown in Figure 1. The largest such pool of users (14% of the entire pool) is in India.

Figure 1 – Distribution of national user populations who use DNSSEC-validating resolvers without support for ECDSA P-256

Missing ECDSA Support by Network

We can take these measurements to a further level of detail by looking at each access network. Using an estimate of the number of users served by each network and then calculating the number of users within each network where DNSSEC validation is performed using RSA but not when using ECDSA we can rank these networks according to the estimated size of these user populations (Table 3)

| AS | Users (est) | Validating | NO ECDSA | Validating | NO ECDSA | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28573 | 21,765,251 | 14,023,996 | 8,168,094 | 64% | 58% | Claro, Brazil |

| 1267 | 9,693,464 | 7,244,741 | 7,044,984 | 74% | 97% | Wind Tre, Italy |

| 8193 | 6,569,136 | 6,270,538 | 5,732,949 | 95% | 91% | BRM, Uzbekistan |

| 9829 | 11,410,595 | 6,342,187 | 5,518,031 | 55% | 87% | BSNL, India |

| 5713 | 5,783,117 | 5,534,273 | 4,567,567 | 95% | 83% | SAIX-NET, South Africa |

| 50710 | 21,899,023 | 20,813,454 | 4,558,142 | 95% | 22% | Earthlink, Iraq |

| 45727 | 9,142,086 | 7,300,558 | 3,192,278 | 79% | 44% | Three, Indonesia |

| 63949 | 13,159,486 | 12,336,200 | 3,088,150 | 93% | 25% | Linode, US |

| 16135 | 9,691,417 | 9,451,412 | 2,820,485 | 97% | 30% | Turkcell, Turkey |

| 37457 | 3,329,390 | 3,251,796 | 2,779,124 | 97% | 85% | Telkom, South Africa |

| 24389 | 8,558,208 | 8,327,046 | 2,306,545 | 97% | 28% | GrameenPhone, Bangladesh |

| 29465 | 29,493,220 | 2,708,701 | 2,168,074 | 9% | 80% | VCG, Nigeria |

| 2860 | 2,734,863 | 2,678,540 | 1,909,484 | 97% | 71% | Nos Communicadoes, Portugal |

| 34984 | 7,671,796 | 7,278,741 | 1,838,380 | 95% | 25% | Tellcom, Turkey |

| 28885 | 2,456,308 | 1,596,600 | 1,501,488 | 65% | 94% | OmanTel, Oman |

| 30873 | 8,772,874 | 5,399,136 | 1,451,867 | 61% | 27% | Yemen Net, Yemen |

| 26615 | 5,474,062 | 2,323,603 | 1,170,759 | 42% | 50% | TIM, Brazil |

| 39891 | 13,376,220 | 13,099,951 | 1,082,068 | 97% | 8% | ALJAWWALSTC, Saudi Arabia |

| 4804 | 3,737,097 | 3,628,318 | 934,926 | 97% | 26% | Microplex, Australia |

| 35819 | 6,725,202 | 6,560,989 | 864,626 | 97% | 13% | Etihad Mobile, Saudi Arabia |

| 49273 | 3,182,458 | 3,072,718 | 843,065 | 96% | 27% | COSCOM, Uzbekistan |

| 24863 | 2,410,271 | 836,623 | 809,397 | 34% | 97% | LINKdotNET, Egypt |

| 6730 | 1,561,571 | 820,486 | 806,933 | 52% | 98% | Sunrise, Switzerland |

| 9038 | 1,896,837 | 797,980 | 771,508 | 42% | 97% | BAT, Jordan |

| 27651 | 2,233,262 | 806,455 | 700,237 | 36% | 87% | ENTEL, Chile |

Table 3 – Variation in support between RSA-1024 and ECDSA P-256 between economies

In this case some further explanation of the columns is warranted. The estimate of the number of users per AS is a highly approximate measurement which divides the national estimate of the number of Internet users across the access ISPs according to the distribution of the sampling measurements. The validating column applies the measured ratio of samples where the end user is observed to successfully DNSSEC-validate DNS responses to the estimate of users per AS. The NO ECDSA Validating column applies the ratio of DNSSEC-validating users who do not perform validating when the DNS record is signed using ECDSA to the Validating user count. These latter two ratios are shown in the next two columns.

Some 15M users who use resolvers that do not support ECDSA (or some 10% of the measured discrepancy) are located in the networks operated by Claro in Brazil and Wind Tre in Italy.

Should we use ECDSA?

In my view these numbers, which are similar in many respects to the outcomes in 2018, are still saying that ECDSA is a usable crypto algorithm for DNSSEC.

It would be good if some of the larger DNS providers who have already taken the steps to add DNSSEC validation to their resolvers updated their crypto libraries by adding support for ECDSA P-256, but the relatively small pool of users who are affected in this manner are small enough that it is insufficient grounds for a signer to delay transitioning from RSA to ECDSA, if that is their intent.

There is an increasing level concern over the continued use of RSA-1024. As the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommended in January 2015: “Zones that initially deployed with RSA using SHA-1 should migrate to RSA (2048-bit RSA key) using SHA-256.” The alternative of using the ECDSA P-256 algorithm for DNSSEC is supported by the observation that this is a far more robust encryption algorithm that can carry public keys and DNS RR signatures in smaller DNS payloads.

All other factors being equal, this seems like a clear choice for me!