I must admit that I’m a keen follower of the analysis work done by Jon Brewer. He manages to pull together excellent research with valuable insights, and I look forward to his presentations. Jon can be found at Telco2.

The second half of this article, looking at the inventory of recent and near future submarine cables in the western Pacific uses his excellent presentation at the recent NZNOG’22 conference in May as the primary source material, and I’d like to thank Jon here for his research into this topic and his insightful presentation.

Jon will be presenting on this topic at APNIC 52 in Singapore in September.

There was a naive idealism in the early days of the Internet that attempted to rise above the tawdry game of politics. Somehow, we thought that we had managed to transcend a whole set of rather messy geopolitical considerations that plagued the telephone world and this new digital space that the Internet was creating was simply not going to play by the old rules. A good example of this thinking was the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace by John Perry Barlow in 1996. I won’t quote it all here, but the assertion “Cyberspace does not lie within your borders” is a pretty good summary. However noble the aspirations of this early Internet may have been, such ideals were not going to last once the Internet assumed the mainstream of the telecommunications industry. Just to remind ourselves, communications is a massive activity sector, currently valued at some 3 Trillion dollars, and it should come as no surprise that this is a highly politicised space.

The early political tensions in communications technology were transatlantic tensions. Virtual circuit-based packet switching technologies, such as X.25 had a strong foundation in Europe, while IP was seen as a US technology. In the mobile communications world Europe quickly embraced GSM technology, while the US market clung to its CDMA system. For a while the mobile market swung in Europe’s favour where Nokia became the dominant provider in the mobile world, but the pendulum swung back to the US with Apple’s iPhone and subsequently Google’s Android platform gaining market ascendency.

In recent years this tension has shifted hemispheres and the Pacific region is now seeing an increase in these political tensions.

A number of countries, including the Unites States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and most recently Canada have announced restrictions on the use of Chinese providers to build domestic service platforms, particularly their 5G mobile networks (Figure 1). Some of China’s biggest technology and telecoms firms have been targeted in recent years by governments in the US and other Western nations over national security concerns.

Figure 1 – BBC News Headline of Canada Announcement – 20 May 2022

These political tensions are not limited to mobile and broadband network platforms. The world of submarine cables in the Pacific is similarly being impacted by these tensions, as illustrated in a presentation by Jon Brewer to the recent NZNOG’22 meeting.

Submarine Cable Models

Funding a submarine cable in the telco era was a process of managed controlled release. Submarine cables were proposed by consortia telco operators, who would effectively become shareholders of a dedicated corporate vehicle that would oversee and finance the construction and operation of the submarine cable. The route of the cable reflected the majority of interests that were represented in that cable company. The cable could be a single point-to-point cable system, a segmented system that breaks out capacity at various waypoints along the cable path, or a multi-drop cable system that supported multiple point-to-point services.

The telco model of cable operation was driven largely by the mismatch between supply and demand in the telephone world. The growth in demand for capacity was largely based on factors of growth in population, growth in various forms of bilateral trade and changes in relative affordability of such services. These growth models are not intrinsically highly elastic. The supply model was based on the observation that the cost of the cable system had a substantial fixed cost component and a far lower variable cost based on cable capacity. The most cost-effective approach was to build the largest capacity cable system that current transmission technologies could support.

The risk here is that of entering cycles of boom and bust. When a new cable system is constructed, then placing the entire capacity inventory of the cable into the market in a single step would swamp the market and cause a price slump. Equally, small increments in demand within a highly committed capacity market would be insufficient to provide a sustainable financial case for a new cable system, so new demands would be forced to compete against existing use models, creating scarcity rentals and price escalation.

The cable consortium model was intended to smooth out this mismatch between the supply and demand models. The cable company would construct a high capacity system, but hold onto this asset and release increments of capacity in response to demand, while attempting to preserve the unit price of pourchased capacity. Individual telephone companies would purchase 15 to 30 year leases of cable capacity (termed an “Indefeasible Right of Use”, or IRU), which would provide a defined capacity from the common cable, and also commit the IRU holder to commit to some proportion of the cable’s operating cost.

The cable company would initially be operated with a high level of debt, but as demand picked up over time the expectation was that this debt would be paid back through IRU purchases, and the company would then shift into generating profit for its owners once it had achieved the break-even level of IRU purchases.

In the telephone world these capacity purchases would normally be made on a “half circuit” model. Each IRU half circuit purchase would need to be matched with another IRU half circuit, such that any full circuit IRU was in effect jointly and equally owned by the two IRU holders.

This framework of cable ownership and operation did not survive the onslaught of Internet-based capacity demand. Since the 1990’s the Internet has been growing along the lines of a demand-pull model of unprecedented proportions. Over the past three decades the aggregate levels of demand for underlying services has scaled up by up to eleven orders of magnitude. Today’s Internet is larger by a factor of a hundred billion or more than the networks of the early 1990’s. This rapid increase in demand exposed shortfalls in the existing supply arrangements, and the Internet’s major infrastructure actors have addressed these issues by working around them. The brokered half circuit model of submarine cable provisioning was rapidly replaced with models of “fully owned” capacity, where a single entity purchased both half circuits in a single IRU transaction, and even to models of “fully owned cables” where the cable company itself was fully owned by a single entity.

Submarine Cable Constraints

However, there are a few aspects of submarine cable systems that have not changed:

- Geology. Cable breaks are disruptive and expensive, and best avoided. The ideal environment for a submarine cable is a deep sea floor path that avoids geologically active areas of the sea floor. Active undersea rift zones, fault zones, and areas that are prone to subsea landslides are best avoided. In general, deeper water is preferred, as shallow water is prone to cable snagging from other maritime activities.

- Distance. Shorter is better. The human factors behind telephony meant that once the end-to-end delay was under 300ms the humans at either end of a conversation perceived the interaction as “immediate”. Computers are far more discriminating, and every millisecond of delays matters. For that reason, shorter cable paths are preferred.

- Territory and Politics. National jurisdictions do not stop at the low tide mark of a territory, but extend out into the sea and the sea floor. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea defined sovereign territorial waters as a 12-mile zone extending out from a country’s coast. Every coastal country has exclusive rights to the oil, gas, and other resources in the seabed up to 200 nautical miles from shore or to the outer edge of the continental margin, whichever is the further, subject to an overall limit of 350 nautical miles (650 km) from the coast or 100 nautical miles (185 km) beyond the 2,500-metre isobath (a line connecting equal points of water depth). What does this mean for submarine cables? The point where the cable enters territorial waters surfaces requires the permission of the country. It also implies that any cable construction and repair operations carried out in these sovereign areas also requires the permission of the country who has exclusive rights to the sea and seafloor.

Cable Systems in the Pacific

For many years the Pacific was a “transit zone” where the major economies that are located on the rim of the Pacific Ocean constructed point-to-point cable systems to provide interconnect. The major cable hubs were on the west coast of North America, Japan, Hong Kong and Singapore.

The result was a “two-speed” Pacific, where the larger economies were linked using high-capacity low delay submarine cable infrastructure, and all the other Pacific communities had no option other than to use geostationary satellite services. It is only in recent years that we’ve seen cable systems proposed to perform “in-fill” to install high speed fibre cables to the smaller communities in the Pacific.

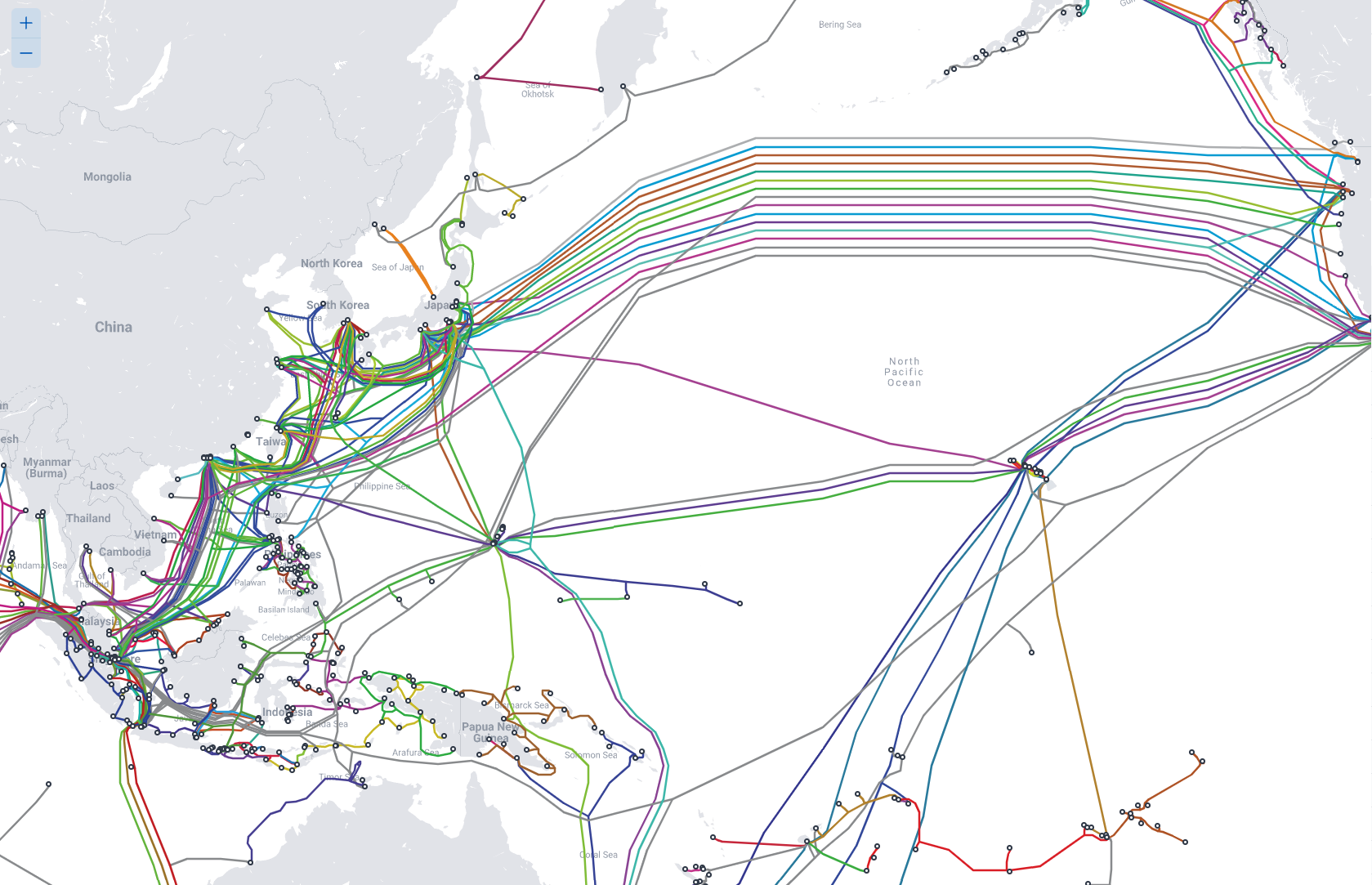

The current picture of cable systems in the Pacific is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Submarine cable systems in the Asia Pacific (from telegeography.com)

The focal points for regional cable connectivity are Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan, and many cables lie under the South China Sea and traverse the Luzon Strait. Singapore acts as a East/West gateway for the cable network and with a small number of exceptions most trans-Pacific cables use a northern route between Japan and the United States.

Recent Pacific Cable Proposals

The rise of content networks and the inexorable shift to cloud-based services has had a major effect of the demand models for carriage capacity. This is not necessarily expressed in the expansion of transit public Internet services, and these days the major content providers including Google, Meta and Amazon are major actors in this space. These changes have created a demand-driven opportunity to extend the submarine cable network in the Asia Pacific region. However, this shift has exposed some unresolved tensions between China and the United States. Let’s look at how these tensions have emerged in a set of recent submarine cable proposals.

Solomons Islands Cable

In 2012 the Asian Development Bank indicated that they would support a proposal to construct a spur on the PPC-1 cable to link the Solomon Islands to Sydney. Progress was slow, and some four years later the Solomons Islands government set up a state-owned cable company to complete the cable. They decided to engage a vendor directly, and the Asian Development bank withdrew its support for the project. In July 2017 Huawei Marine announced the signing of a contract with the Solomon Islands Submarine Cable Company to design and construct a 2.5Tb cable link between Honiara and Sydney, using a 4,000km submarine cable.

This project was seen as a step too far for the Australians, who were reported to be unwilling to have Chinese equipment interconnected with the Australia network. One year later, in August 2018, Australia announced that it would fund a cable project, the Coral Sea Cable system, that would link Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands to Sydney, with the project being managed by an Australian entity, Vocus. They then selected Alcatel Submarine Networks as its cable provider and the system was completed in December 2019.

East Micronesia Cable System

Support from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank were proposed in 2017 for a cable system that would leverage an existing cable system between Guam and Micronesia and the Marshall Islands (HANTRU-1) to extend this with a link from Phonpei to Kosrae in Micronesia, Nauru and Tawawa, the capital of Kiribati. Alcatel Submarine, Huawei Marine and NEC all lodged bids to construct this cable.

A Reuters news item in late 2020 reported that the United State warned Pacific Island nations about the security threats posed by Huawei Marines “cut price bid” to construct this cable, echoing earlier concerns voiced by Nauru on the potential roles of Huawei Marine. The report mentioned the requirement placed on all Chinese firms to cooperate with China’s intelligence and security services, and the potential implications this had regional security in this part of the Pacific. This was picked up by the United States, who voiced a similar warning on the potential security threats posed by the Huawei Marine bid to construct this cable. By mid 20201 the entire project had reached a stalemate and the project was ditched.

In a replay of the Solomon Islands Cable, in December 2021 Australia, Japan and the United States announced plans to fund a new cable linking the same three locations to HANTRU-1.

Pacific Light Cable Network

Many east-west trans-Pacific cables traverse the Luzon Strait, located between Taiwan and the Phillippines. This is one of the few deep water entrances East Asia. Futher north, the cable would have to run though the shallow continental shelf waters of the Taiwan Strait, and further south would mean a lengthy detour through the Philippines and the South China Sea to reach Hong Kong.

The Pacific Light Cable Network was a partnership between Google, Facebook and the Chinese Dr Peng Group, proposed to use 12,800 km of fiber and an estimated cable capacity of 120 Tbps, making it the highest-capacity trans-Pacific route at the time (2018), and the first direct Los Angeles to Hong Kong connection. The cable was completed in 2018, but a US Justice Department committee blocked approval of the Hong Kong connection on the US side, citing “Hong Kong’s sweeping national security law and Beijing’s destruction of the city’s high degree of autonomy as a cause for concern, noting that the cable’s Hong Kong landing station could expose US communications traffic to collection by the PRC.”

In early 2022 the US FCC approved a license for a modified cable system that activated the fibre pairs between Los Angeles and Balen in the Philippines and Toucheng in Taiwai. The other four fibre pairs are unlit under the terms of this FCC approval.

Hong Kong – America Cable (HK-A)

The Hong Kong-America Cable System was a 6-fiber-pair submarine cable proposal, intending connecting Hong Kong and Taiwan with the U.S. directly, with initial design capacity of 12.8 Tbps per fiber pair (for a total of 76.8 Tbps) using 100Gbps coherent DWDM technology.

The HKA Consortium consisted of Facebook, China Telecom, China Unicom, RTI Express, Tata Communication and Telstra. The supply contract was awarded to Alcatel Submarine. The HKA Consortium and ASN officially announced the launch of HKA cable project at PTC 2018. The application to land the cable in the US to the FCC was withdrawn in March 2021.

Hong Kong – Guam (HK-G)

The Hong Kong-Guam (HK-G) cable system was originally proposed in 2012 as a 3,700 kilometer undersea cable connecting Hong Kong and to Guam. The HK-G cable system was proposed to have 4 fiber pairs, with design capacity of 48 Tbps (12 Tbps per fiber pair).

The application to the FCC land the cable in Guam was withdrawn in November 2020.

Bay to Bay Express (BtoBE)

The BtoBE consortium was composed of China Mobile International, Facebook and Amazon. It was proposed to be 15,400 km trans-pacific optical fiber submarine cable system connecting Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong and the US. The BtoBE cable system was to supplied by NEC.

In light of the US no longer approving landings with respect to direct connections between the United States and Hong Kong, the BtoBE consortium withdrew the application for cable landing license on September 10, 2020.

The Next Round of Cables

The demand for further capacity across the Pacific Ocean continues, but with the current US position on withholding US landing approval for cables that terminate in China or Hong Kong, and with the unresolved international issues in the South China Sea any new cable proposals that cross the Pacific either have to use the northern routes and connect to Japan or use a more southerly route that passes south of Kalimantan to reach Singapore.

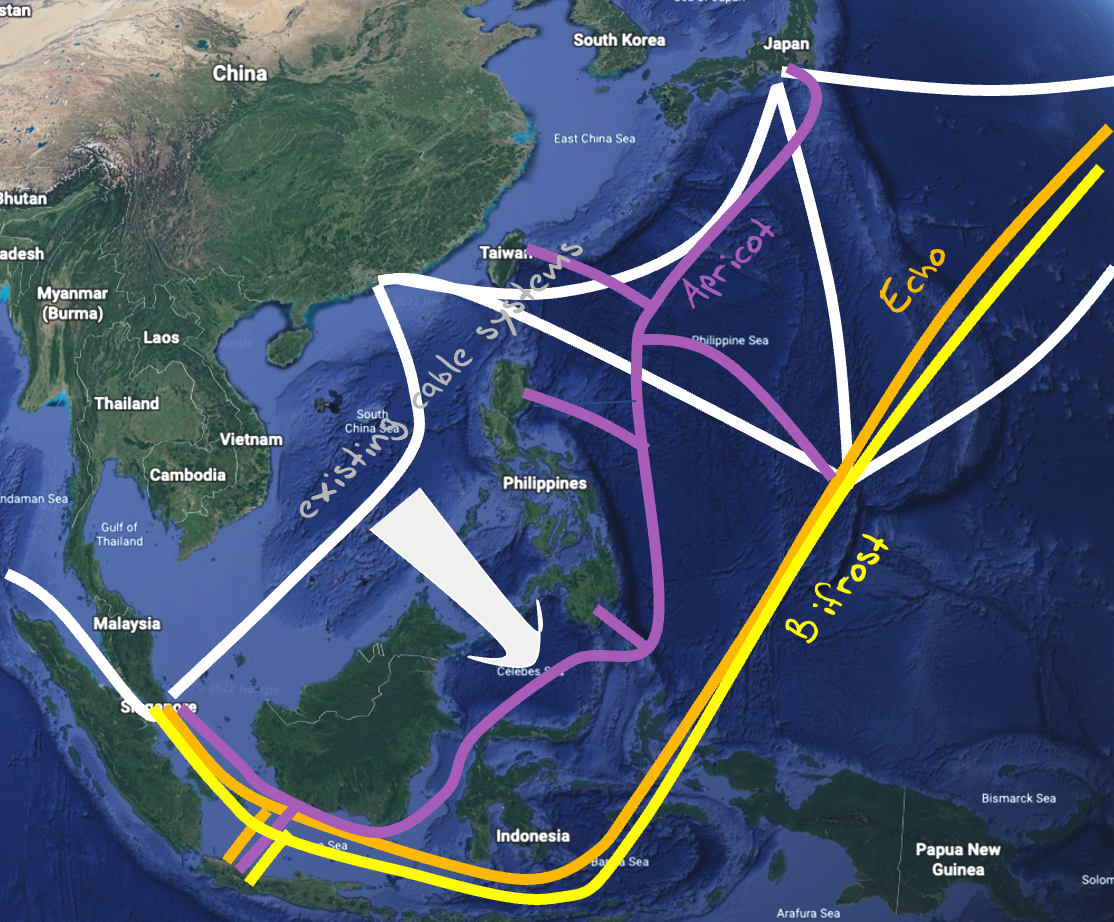

Apricot

Apricot is a 12,000 km cable system that provides north-south connectivity along the western Pacific Rim, with landing points in Japan, Taiwan, Guan, Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore and a capacity of some 190Tbps. The Apricot consortium comprises Facebook, Google, NTT, Chunghwa Telecom (CHT) and PLDT. The cable system is being constructed by NTT.

Echo

Echo is a 144Tbps 16,206 km east-west trans-Pacific cable system connecting Singapore and Indonesia to the US, with a branching connection to Guam. The cable system will be supplied by NEC. Google and Facebook will own half the cable capacity each. The current ready for service date is listed as 2023.

This is the first direct Singapore – US cable connection, but it’s by no means the last.

Bifrost

Bifrost is an East-West trans-Pacific cable system connecting Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines to the US with a branching connection to Guam. The cable is being constructed by Alcatel Submarine, with a ready for service date is listed as 2024. The cable is a 12 pair system.

The Bifrost consortium comprises Facebook, PT. Telekomunikasi Indonesia International (Telin), and Keppel Telecommunications & Transportation Limited (Keppel T&T).

The New Cable Map of the Pacific

There is a realignment in the western Pacific with new submarine communications systems shifting east from the South China Sea and the Luzon Strait and instead using the Celebes Sea, the Banda Sea and the Philippine Sea.

Hong Kong will no longer be the focal point for western Pacific connections in the coming years, and instead we appear to be concentrating on Japan, Guam and Singapore, with Guam becoming a highly critical nexus of regional infrastructure. (Figure 3)

Figure 3 – New High Capacity Trans-Pacific Cables

The open question here is how China will respond to these changes. This is not just a cable route question, or a question about the future roles of Chinese technology providers such as Huawei and ZTE in the global markets, but a larger question about the way in which the China-based digital giants, such as Ali Baba and Ten Cent will engage in these global digital markets. And for such questions there is much that is shrouded in a veil of uncertainty about the near- and medium-term futures for our world. As has happened many times in history, the introduction of radically new technologies into human society, and the massive societal changes they induce, creates change, uncertainty and disruption to the old ways of doing things. In such times any predictions of the future are little more than wild guesses!